Finding Einstein’s Brain

Rutgers professor pursues answers to what makes a genius

‘Why they were never offered for analysis by the scientific community and essentially remained hidden has never been understood.’Frederick Lepore, Professor, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

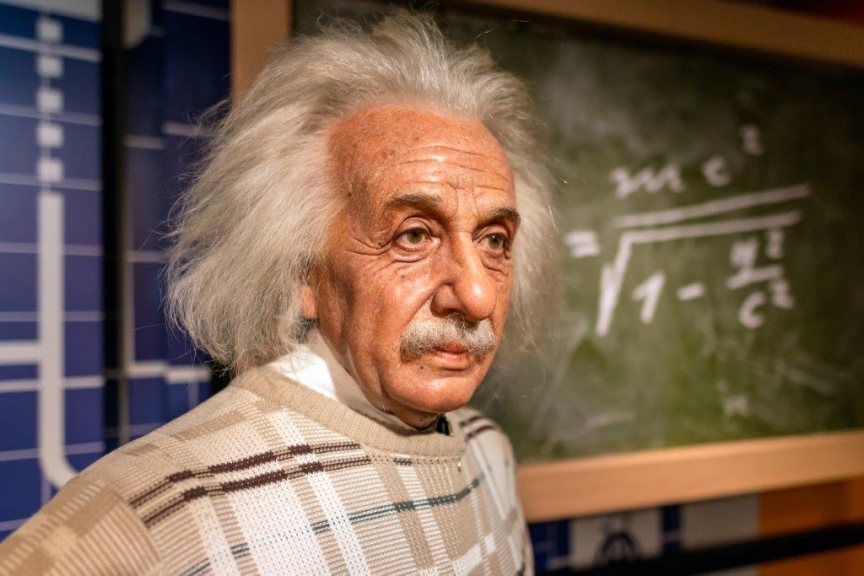

Since the death of Albert Einstein 60 years ago, the theoretical physicist's brain has been the subject of awe, speculation and scholarly research. Frederick Lepore is more fascinated than most.

Lepore, a Rutgers clinical neurologist, unearthed a trove of dozens of photographs and nearly 600 histologic microscope slides of Einstein’s brain – more than 50 years after they were presumed lost following the famous physicist’s death and immediate autopsy in 1955.

Unbeknownst to the scientific community, the photos sat gathering dust in boxes in a home in Titusville, New Jersey, where Thomas Harvey, who performed Einstein’s autopsy in Princeton, had lived with his companion Cleora Wheatley.

“Why they were never offered for analysis by the scientific community and essentially remained hidden has never been understood,” said Lepore, a professor at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School whose fascination with Einstein led him to keep general track of Harvey until his death in 2007.

In 2007, paleoanthropologist Dean Falk contacted Lepore, hoping to enlist his assistance in landing the lost photos that detailed Einstein’s brain. After performing the autopsy, Harvey had removed, photographed and eventually sectioned the brain into 240 blocks from which histological slides were prepared.

Lepore spoke with Wheatley in 2009, beginning a journey to gain access to the photographs that became almost as complex as the study of Einstein’s brain, has gained new attention this year as the 100th anniversary of Einstein’s theory of general relativity which shaped our concepts of space, time and gravity is celebrated this month.

But the conversation with Wheatley proved unproductive; Lepore was denied the photos for research and publication.

In 2011, Lepore learned that the Harvey family had donated the photos to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland, where they were archived though unavailable for scholarly access.

Lepore tried again. Though the museum would not allow him to remove any materials, Lepore was given eight hours to take his own photos of Harvey’s original 8x10 glossy images of Einstein’s brain shot 56 years earlier.

“Once we had the photos, you could start to see things that define and outline the anatomy,” says Lepore. “It was huge.”

Some of those photos first appeared as illustrations accompanying a paper Lepore co-authored with Falk in the journal Brain in 2012.

“Fifty thousand people downloaded it,” says Lepore, who is writing a book, Finding Einstein’s Brain, which explores the anatomy of genius and recounts the pursuit. “The interest in the subject is incredible.”

In examining the photographs, Falk and Lepore found Einstein’s prefrontal cortex extraordinary, not in size, but in its makeup. The right prefrontal area included a fourth gyrus, or ridge, one more than typical, which, Lepore said, may have contributed to some of his remarkable cognitive abilities.

In addition, the researchers theorized that Einstein’s unusual-looking parietal lobes offered clues to Einstein’s visuospatial and mathematical skills.

“Einstein’s brain has typical frontal and occipital shape asymmetries (petalias) and grossly asymmetrical inferior and superior parietal lobules,” Lepore says. “Contrary to the literature, Einstein’s brain is not spherical.”

Not all in the scientific community have been receptive to Lepore’s and Falk’s findings. Some researchers argue that they provided a detour on the track toward understanding what the physical nature of Einstein’s brain represents and that Einstein’s brain was not exceptional.

To the argument that the unique features in Einstein’s brain were connected with his genius goes beyond what the evidence shows, Lepore says, “What we did in the paper was thoroughly document the variant anatomy of the brain of arguably one of the world’s greatest minds. End of story. It’s for others to connect the dots.”

“In a perfect world, the next step would be to study the brains of other superior intellects like him and compare them,” said Lepore. “That remains a daunting task.”

For media inquiries, contact Jeff Tolvin at 973-972-4501 or jeff.tolvin@rutgers.edu