How Hip-Hop Pedagogy Is Transforming Classroom Learning

A national research association honors a Rutgers education professor for her innovative approach to empowering students and challenging inequities

Lauren Leigh Kelly, an associate professor in the Graduate School of Education at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, was recently recognized by the American Educational Research Association (AERA) as one of the nation's top teacher educators.

A leading scholar in hip-hop pedagogy, Kelly studies how hip-hop culture can challenge oppression, racism and isolation in society as well as strengthen learning outcomes.

In 2024, Kelly published Teaching with Hip Hop in the 7-12 Grade Classroom, a guide for using hip hop music and culture to support student identity and foster critical thinking. She is the co-editor of the Bloomsbury Handbook of Hip Hop Pedagogy. At Rutgers, her course, “Introduction to Hip Hop Education,” is among the Graduate School of Education’s most popular.

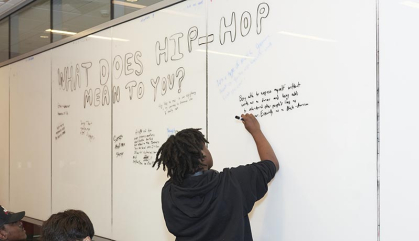

Kelly also is the founder of the Hip Hop Youth Research and Activism (HHYRA) Conference, an annual youth-led event that empowers students as agents in their own learning. The 7th HHYRA conference was held at Rutgers on April 11.

Kelly discussed how traditional approaches to education have left many students outside of the conversations that deeply impact their lives, and why she believes a hip-hop pedagogy can help reset the imbalance.

What inspired you to create the Hip Hop Youth Research and Activism Conference at Rutgers?

Most of the literature on hip-hop tends to focus on urban areas, on cities, on predominantly Black and Latinx youth, even though we know that statistically, hip-hop is most commercially consumed by suburban white teenagers. In fact, it’s documented to be one of the most listened to genres of music in the world. To relegate hip-hop education to something that’s only for Black and brown youth and only in urban areas, is dangerously inaccurate.

As educators, we should be working to disrupt things like oppression and racism and isolation. That’s why I started the HHYRA conference – to have conversations with the people who are most listening to hip-hop music about what they're listening to, and why they're listening to it. What are they hearing? How is it impacting their understanding of the world?

In 2019, after several years of fine tuning, we brought the conference to Rutgers. We recruited young people to put their stamp on things, to decide who should be teaching workshops, what the themes should be. If HHYRA is for them, it should also be by them.

Where did the idea come from?

HHYRA was inspired by Dr. Ernest Morrell, who was one of my professors and advisers at Teachers College at Columbia University, where I did my doctoral studies. When I was teaching a high school hip-hop literature course, Dr. Morrell recommended that I bring my students to campus for a one-day workshop focused on hip-hop and youth activism in collaboration with teaching artists and students from across New York City. Doing this really opened my mind to all the things that I could do as an educator to cultivate students’ critical learning and community engagement.

Why is hip-hop such a powerful teaching tool, in your view?

There's no other space that does what hip-hop can do in bringing together the study of culture with an understanding of history, and particularly the history of marginalized communities in the U.S.

Hip-hop as we know it started in New York City as an alternative to gang violence. DJ Afrika Bambaataa helped transform battles that were physically violent into an art form that allowed people to battle through their bodies, through dancing, through styling, through having DJ crews and waging DJ battles.

The early protagonists were told they had nothing to contribute to society, that they were disposable. They had to find a way to not just survive, but to thrive. That was hip-hop. That was breaking in the subway on cardboard, coming together at jams. If hip-hop was your outlet, maybe you didn't have a job, maybe you didn't have a home or a safe home. But you had this skill, and people were celebrating you for it.

One of my favorite books is Jeff Chang's, Can't Stop Won't Stop, which is a hip-hop history, but it's also American history told through the lens of hip-hop. If you understand hip-hop history, you understand how culture evolves, how it forms, how it shifts, how it connects to people, how it lives and resonates.

But hip-hop can teach young people something else: It can help students think critically about what and how they can contribute to their communities. For too long, we've told students that you go to college to get a job, earn money, buy a house, etc. But education in the post-pandemic era fractured that myth and demonstrated that this structure doesn’t work for everyone. Teaching through hip-hop can show how important purpose is in life and reinforce the idea that we are masters of our own destiny.

What do you hope your students learn from hip-hop?

My ultimate goal is to create a pipeline to recruit more diverse youth to consider themselves educators or leaders. That may not necessarily mean being a teacher; it could be a professor, a school counselor, a student affairs officer. But I really want young people to be able to show up in this space and think differently around school and education, which ultimately might help diversify the teaching force in America.

You were just named an outstanding early career educator by the American Educational Research Association. Tell me about that recognition.

It was such an honor to receive this award for my teaching. Sure, I'm a scholar, and some days, I identify that way. But I'm a teacher first. I get excited helping teachers in the classroom build community, support students and put critical thinking at the forefront of their pedagogy. To be recognized by an organization charged with improving the educational process is, to me, the ultimate honor.