Inside the Harlem Uprising of 1964

James Powell and his classmates were waiting for summer school to begin on July 16, 1964 when a white building superintendent, reportedly tired of the Black teens gathering near his stoop, turned a hose on them. Several students chased the super to his apartment, and Powell banged on the door.

The commotion on New York’s East 76th Street caught the attention of Thomas Gilligan, a white, off-duty police lieutenant. Attempting to intervene, Gilligan claimed Powell lunged at him with a knife and refused orders to drop it. He fired multiple shots and killed the 15-year-old, sparking six days of violent protests that jolted the city.

“The police marshalled an unnecessarily aggressive response to the protestors, arresting and viciously beating many in the crowd,” said Christopher Hayes, an urban historian in the School of Management and Labor Relations. “This fighting quickly exploded into a neighborhood uprising against police violence and racial inequality, starting in Harlem and jumping the East River into Bedford-Stuyvesant.

"When it was over, the police had arrested hundreds, injured thousands, and killed at least one man. Hundreds of businesses were looted or damaged.”

Powell’s death poured gasoline on a long-smoldering fire. Segregated in run-down neighborhoods, denied employment opportunities, and mistreated by police, many Black New Yorkers were fed-up long before Gilligan pulled the trigger on that hot July morning. The protests harnessed their pent-up anger and challenged New York’s progressive image.

“It was the first urban rebellion of the 1960s and set a template for nearly all that would come after,” Hayes said.

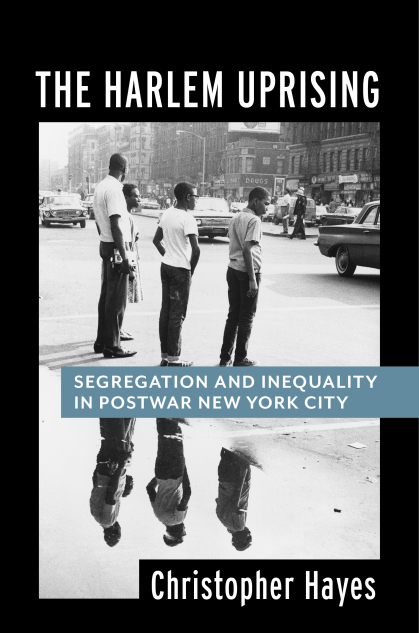

Hayes, who earned his Ph.D. in American History at Rutgers in 2012, spent more than a decade researching the causes and impact of the protests for his new book, The Harlem Uprising: Segregation and Inequality in Postwar New York City.

It’s a timely publication. Eric Adams, sworn-in as mayor less than two months ago, is a former NYPD captain with plans for reforming the department.

“If Mayor Adams can’t get real change done, I suspect no one will,” Hayes said. “He was beaten by NYPD officers at age 15 and joined the department to reform it from within. He knows the job from officer on up to captain, spending more than a decade of his career challenging leadership and several mayors over racist practices and unwarranted violence.”

But as Hayes argued in a recent Slate op-ed, Adams can expect stiff opposition from the city’s powerful police unions, led by the Police Benevolent Association (PBA), which has a long history of resisting reform.

Falling Short of Reform

Two months after James Powell slumped to the pavement on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, a grand jury cleared Lt. Gilligan of wrongdoing. Witnesses gave conflicting accounts as to whether Powell had a knife during the encounter.

Mayor John Lindsay took a step toward reform in 1966 when he appointed four civilians to the previously all-police Civilian Complaint Review Board, the group tasked with investigating complaints against officers and making disciplinary recommendations to the police commissioner.

But in a little-known episode that Hayes explores at length in his book, the PBA rallied officers, business leaders, elected officials, and the public against Lindsay’s action and overturned it in a matter of months.

“The PBA put the issue of civilian oversight up for a referendum,” Hayes said. “Their professionally-produced campaign of fear and racism succeeded fantastically, banning civilian oversight of the police by a 2-1 margin.”

Civilians did not return to the CCRB for more than 20 years.

After Lindsay, comprehensive reform remained elusive. Racial disparities under the “stop-and-frisk” policy championed by Mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, and the police killings of other Black New Yorkers, including Amadou Diallo in 1999 and Sean Bell in 2006, drew widespread condemnation.

On July 17, 2014, nearly 50 years to the day after Powell’s death, a white NYPD officer placed a Black man, Eric Garner, in a chokehold while attempting to arrest him on suspicion of selling loose cigarettes. Garner pleaded, “I can’t breathe,” 11 times before dying. The officer, Daniel Pantaleo, was fired after a disciplinary process that dragged on for five years, and the police union intervened to prevent systemic reform.

“The city passed a law criminalizing police chokeholds,” Hayes said. “The PBA successfully had it struck down in court.”

The police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020 seemed to change everything, prompting unprecedented scrutiny of systemic racism and police brutality across the country. But Hayes is skeptical of the lasting impact and believes the odds are still stacked against reform.

“Right now, it’s hard to see many results from our much-vaunted ‘racial reckoning,’” Hayes said. “We’ve seen this pattern repeat itself for generations. It’s going to take more than supportive statements to effect real change, but maybe Eric Adams will be the one who finally gets it done in New York. We’ll see.”