In New Documentary, Rutgers Scholar Sheds Light on a Civil Rights Pathbreaker

Brittney Cooper provides commentary, expertise in My Name Is Pauli Murray

As a civil rights activist, attorney and clergy member, Pauli Murray could be called prophetic, a fitting description for the first Black woman to become a priest of the Episcopal Church, which in 2018 enshrined Murray as a saint, according to Rutgers University scholar Brittney Cooper.

“Murray was a pioneer for racial, gender and socioeconomic equality,” Cooper said. “She led successful non-violent desegregation movements in the 1940s, nearly 20 years before those tactics would be used in the broader civil rights struggle. As someone whom today we would call a trans or non-binary person, she advocated in the '30s and '40s for gender affirmation procedures like hormone therapy, long before they became standard medical protocols. She was a critical advocate for making sure the word ‘sex’ was included in the 1964 Civil Rights Act. As an attorney, she formulated the legal theory of the Brown v. Board of Education case, helped argue the case that overturned the all-white, all-male jury system in the United States, and won many other civil rights victories.”

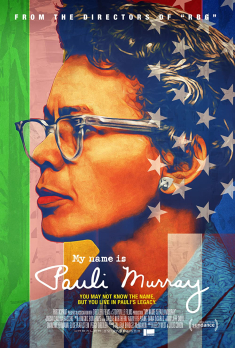

This week marks the Sundance Film Festival premiere of My Name Is Pauli Murray, a documentary by Betsy West and Julie Cohen, the filmmakers behind RBG, the Oscar-nominated 2018 documentary about U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Cooper is featured prominently throughout the 90-minute film as an expert commentator on Murray, who died in 1985 at age 74 and was a subject of Cooper’s book Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. The film also includes footage of Cooper giving a lecture to her students in the "Introduction to Gender, Race and Sexuality" course she teaches as an associate professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies, and of Africana studies.

The filmmakers approached Cooper after hearing her speak at a 2018 event, hosted by Murray biographer Patricia Bell-Scott, which celebrated the re-publication of Murray’s memoir Song in a Weary Throat and poetry collection Dark Testament.

“Murray was a participant in almost every major movement for social change in the 20th century. Murray didn’t take no for an answer. She believed that the law could be used for social good; she believed and pushed for America to live up to its promise; and she believed that race, gender and socioeconomic status should be dismantled as barriers to social progress,” Cooper said.

Cooper said Murray deserves recognition as a household name and that people who share Murray’s Black, gender nonconforming or queer identities deserve to know of her life and accomplishments.

Murray, born in Baltimore, followed her decades of legal advocacy by becoming an Episcopal priest in 1977, the first year the church ordained any women. In 1940, 16 years before Rosa Parks began the Montgomery bus boycott, Murray sat in the whites-only section of a Virginia bus and was arrested for violating state segregation laws, an incident that inspired her to become a civil rights lawyer. She encountered sexism at the Howard University Law School, where she graduated first in her class but was denied post-graduate work due to her gender.

In 1950, she wrote States’ Laws on Race and Color, which Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall called the “Bible” of Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court case that ruled public school segregation unconstitutional. In 1966, she co-founded the National Organization for Women. In 1971, Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg named her as a co-author of a legal brief in a landmark case on gender discrimination. Drawn to the ministry, in 1977 she became one of the first generation of Episcopal women priests and the first Black woman priest. Based on Murray’s descriptions of her gender identity and sexuality, several scholars have identified her as transgender.

“The point I make with my students in the documentary is that the diversity of our classroom, with students of all different races, genders, class backgrounds and sexual identities, is a direct result of Murray’s legal and social advocacy for an inclusive world. We could not be in the classroom together today but for Pauli Murray.

“If still here today, she would resonate with the worldwide struggles for Black dignity and gender dignity. She would also welcome the contemporary re-imaginings of gender categories since she found binary categories of male/female so restricting throughout her life,” Cooper said.