Jochen Hellbeck’s book among first to give voice to Soviet defenders of the city

Jochen Hellbeck, professor of history and a specialist in Russian history at Rutgers, has written a book that tells the stories of the people who lived through this decisive battle of World War II and its aftermath. The Stalingrad Protocols: Soviet Eyewitness Reports of the Battle (S. Fischer Verlag 2012), is based on more than 200 oral histories – ranging from interviews with field marshals and privates to nurses to riflemen and collected by Soviet historians, organized as the Commission on the History of the Great Patriotic War. The Soviet government subsequently suppressed the interviews, and they remained locked in government archives until just recently. The book has been published in German; an English publication is forthcoming.

Rutgers Today: There have been many books written about the Battle of Stalingrad. What's new

Jochen Hellbeck: Books on the battle are legion; an abundance of soldierly voices have been preserved in letters and diaries. But most of these voices belong to German soldiers. The Soviet side has been curiously silent, largely because of military and political censorship regulations during and after the war. Some Western historians also believe that Red Army soldiers were less sophisticated and could not express themselves well. But as we can see from these oral histories, that’s just not true. Stalingrad Protocols features rich interviews with dozens of Soviet soldiers and other defenders of Stalingrad, interviews recorded during the final stage of the battle and its immediate aftermath. The steno graphed transcripts are so lively; they have the feel of audiotaped conversations.

Rutgers Today: Why should we care about how soldiers, Soviet or German, felt about that battle 70 years ago? Indeed, since Hitler and Stalin are long gone; why should we care about the battle at all?

Rutgers Today: Given the nature of Stalin's regime, do you think the people interviewed by the Historical Commission back in 1942-1943 were candid? After all, Alexander Solzhenitsyn ended up in the Gulag for eight years just for making fun of Stalin's mustache.

Hellbeck: The interviews are surprisingly candid. Two factors, I believe, account for this. One is the very careful methodology employed by the historical commission. Its head, Isaak Mints, reminded his co-workers how important it is to create an atmosphere of trust, to get people to open up and reveal their personalities. He favored open questions and a format that would capture as many individual specifics as possible. Secondly, the interviews were conducted in January or February 1943, the time of an unprecedented triumph over the Germans. Red Army soldiers would want to inscribe themselves into history now that the victory was theirs. In general, the war years were a relatively liberal period for Soviet citizens. The regime tightened the screws toward the end of the war, and Solzhenitsyn fell victim to this. This also explains why the Stalingrad Protocols were suppressed after the war. They were too candid, too individualized. After the war, Stalin wanted to claim victory for only himself.

Rutgers Today: What do we learn from the publication of the 1942-1943 oral history transcripts that sheds new light on the war, the battle and the world as it was at the time?

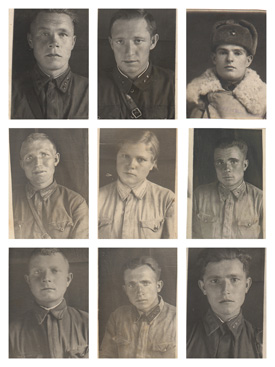

Hellbeck: These transcripts humanize the defenders of Stalingrad. We now have the live voices of army commanders as well as soldiers, political officers and nurses. Even a kitchen worker was interviewed. The interviews also refute the cliché of the simple, brutish “Russian peasant soldier” that still abounds in historical scholarship – a cliché that owes more to Tolstoy’s 19th century writings than to the Soviet realities of the 1940s. Many of the interviewed soldiers were members of the Communist Youth organization, and hardly any of them identified as a peasant. In fact, the Communist party embarked on a huge membership drive during the battle of Stalingrad, and its appeals to defend the “Soviet homeland” and fight back the “fascist invaders” registered widely. In addition to the military side, interviews with surviving inhabitants of Stalingrad document the horrors of the war and of the German occupation that they had to endure.

Rutgers Today: You're a German. How did you become an historian of Russia?

Hellbeck: I am from West Germany, but as a teenager during the early 1980, I lived in East Berlin for a few years. My father worked as a West German diplomat in East Germany, and we all lived there. That’s when I became curious about the Soviet Union and began to learn Russian. My first trip to Moscow was in 1986, I remember we had to translate speeches by Mikhail Gorbachev who had just come to power. The Perestroika years were a very exciting time, and my passion for Russia and its history stems from this period.

Media Contact: Ken Branson

732-932-7084, ext. 633

E-mail: kbranson@ur.rutgers.edu