Rosemarie Pena is one of thousands of children born to African-American GIs and white German women after World War II

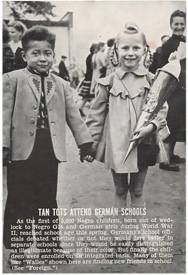

A magazine image of a so-called "brown baby,'' left, attending school in Germany.

She grew up in Willingboro, New Jersey as Wanda Lynn Haymon, the only child of an African-American mother and father who made her feel special and loved.

But when relatives whispered at family gatherings, she knew they were talking about her. One day she asked her parents if she was adopted.

"Do you feel adopted?" they answered.

She did, but had no proof until 1994, when Wanda Lynn discovered that she was born Rosemarie Larey in Viernheim, Germany, the daughter of a black soldier and German mother. Although she was born in 1956, just 11 years earlier, Nazis, who regarded blacks as racially inferior, sent some of the estimated 25,000 Afro-Germans to concentration camps. Many were subject to medical experiments or were forcibly sterilized. Others simply disappeared.

After the war, the stigma of bearing a biracial child was so great that many mothers brought their children to orphanages, which often placed them with African-American families in the United States.

Today, Rosemarie Pena (her married name) is completing her master’s degree at Rutgers-Camden, in the Department of Childhood Studies, researching the history of “brown babies,’’ as they were known at the time of their birth, as well as people who identify as Afro-German around the world.

Pena also heads the Black German Cultural Society of New Jersey, an academic organization that connects Afro-Germans internationally. Its mission is to document Black Germans and inform others about their history. For post-war adoptees like Pena, the society helps them find closure and connects them with others who share their experience.

In Germany, blacks comprise only 2 percent of the population and are spread out geographically, Pena says. As leader of the black German cultural society, she has connected with a new generation of Afro Germans. Despite their German nationality, they are often regarded as outsiders, whose German accents draw looks of confusion.

“A lot of people think saying you’re black German is an oxymoron. People see them as foreigners, even when they were born there and have German nationality,” Pena says.

Pena was abandoned by her mother as in infant, left on the snow-covered steps of a black military family stationed in Germany. They brought her to an orphanage and eventually she was adopted by the Haymons. Pena’s childhood in Willingboro was happy – except for the nagging feeling that her mom and dad weren’t her birth parents.

Rosemarie Pena as a baby after her adoption.

In 1995, she tracked down her birth mother and learned some details about her infancy and abandonment. She invited her birth mother to stay with her for two weeks in the hope of establishing a relationship. Her mother accepted, but the two never grew close. “We were strangers,’’ says Pena.

Pena’s birth mother, who had two additional daughters that she raised in Texas, never revealed the name of her father and claimed to have been raped, but Pena is skeptical.

Over time, her mother revealed details about her childhood, giving Pena an understanding of her mother’s inability to reconnect with her. Pena’s birth mother, who is Danish, was a concentration camp survivor whose father was shot to death before her eyes. She didn’t seem to know why it happened, but Pena thinks it might have been because he was a resister. “What she endured was really traumatic, and that followed her and followed her children,’’ Pena says.

Rosemarie Pena was born to a German mother and a black GI during World War II. Pena was adopted by an African-American family after her mother abandoned her in post-war Germany.

Although she was unable to bond with her birth mother, after Pena learned her birth name had never been legally changed in the U.S., she stopped calling herself Wanda Lynn and reverted to her original name, Rosemarie. “I think it was part of reclaiming my true identity,’’ she says. “I didn’t want to cause my parents pain or disappoint them, but I wanted to be my authentic self.’’

Pena also continued her journey in search of her roots. She completed a second bachelor’s degree in German in 2010 after attending an annual meeting of an Afro-German group in Germany. It was a turning point. “I felt like my soul was at home,’’ she says.

Pena has headed the Black Cultural German Society for more than a decade. Last year, the organization incorporated in New Jersey. In August, the group will have its second convention on the black German experience at Barnard College-Columbia University. Since her involvement with the society, Pena has heard many stories from black Germans born long before World War II and during the post-war era.

Hans Massaqoui, a former managing editor at Jet and Ebony magazines, grew up in Nazi Germany with an African father and a German mom. As a child, he wanted to wear a swastika and join the Hitler Youth, like his classmates. He soon discovered why he was barred from the group, but remained in Germany with his mother and managed to survive the war.

Pena’s friend and fellow board member Carmen Geschke grew up in Germany without ever being told that her father was black. She knew that her mother was shunned, and she knew that she was different. She was teased because of her tan complexion and kinky hair. But it wasn’t until her teens that she realized she was black.

Once she moved to the United States, her sense of alienation continued, but she was grateful to find a group of black Germans in Detroit, where she moved.

“The biggest issue most of us have had is the need to belong,’’ says Geschke, who now lives in Greenville, South Carolina.

The Black German Cultural Society provided her with community and helped Geschke gain a sense of pride about her black German heritage. “It opened up my world. I’m not some poor little black German girl who is alone. I’m part of a group and I’m proud of that group, Geschke says. “Many of us have good stories. We have mastered our lives and we’re happy.’’

For Pena, stories like this are proof that the organization is achieving its goals.

“Because I survived physically and emotionally, I feel it’s my mission to do what I do,’’ she says. “That’s what motivates me and drives me to continue.’’