Redefining the Meaning of Disability

This year in recognition of National Disability Awareness Month, we invited members of the Rutgers community to reflect on one thing they want people to know about their experience as a person with a disability, or as a caretaker for someone with a disability, and how they want to be seen by the world. Here is what they had to say.

Vidhi Raval

Class of 2025

School of Communication and Information

Rutgers-New Brunswick

As an individual with a disability, specifically visual impairment, I’ve often been treated with excessive sympathy; with others going out of their way, instead of simply providing the information I asked for. Other times, people go to the opposite extreme, almost ignoring me entirely, and making me feel invisible. I don’t want to be seen as someone who needs constant assistance, but also don’t want to be overlooked or ignored. I want people to understand that I face visual challenges daily, but they don’t define me. I should be treated with the same respect as others.

I’ve been pulled by the arm through airports when I only asked for directions to the entrance or exit while independently traveling, and I’ve had “friends” laugh and say, “I’m sorry, I forgot you were ‘blind,’” as I struggled to navigate uneven pathways at night. While I may not look like I have a visual impairment, that does not mean that I don’t face difficulties with navigation or seeing things at a distance. I want people to understand that just because I don’t constantly mention my disability, doesn’t mean my struggles aren’t real. I don’t want others to minimize the challenges I face simply because they aren’t always visible. Additionally, the best way to support me is to ask if I need help, rather than assuming I do. I believe that practicing independence is crucial in college, and I want to learn how to navigate difficulties instead of someone constantly trying to hold my hand.

In the past, I’ve tried to conceal my disability to make others feel more comfortable and because I didn’t want it to define every interaction. However, I want to speak openly about my visual struggles without fearing that friends or partners will find me strange or frustrating. Asking for accommodations or help shouldn’t feel awkward or uncomfortable—it’s a normal part of life, and something I’m still learning to accept. Being open and honest with those around you is important. Only then can they truly understand you.

Rosann Richards

Director of Business Services

Rutgers-Newark

As a caregiver to an adult with autism, one of the most important lessons I’ve learned is that finding community is essential. At events promoting my children’s book, Tylor’s Authentic Smile: A Sibling Book About Autism, I’ve met so many people also touched by autism and other disabilities. It’s been a reminder that we, as caregivers, don’t have to do this alone and we are not alone.

When my son Tylor was diagnosed with autism in December 2005, the uncertainty was overwhelming, and most days it still is. The unknown weighed heavily on our family and was often terrifying. I began seeking resources and connections. Nineteen years ago, I joined a group of moms at a special needs music therapy and tumble class. We would meet weekly for our children to learn play skills and socialize. It quickly became a way to bond, share and support one another. Fast forward to 2024, and we just had our annual moms' dinner, where we shared updates on our children, exchanged guidance on their life transitions, and offered each other support. That group of women is my lifeline and the reason I gained confidence in this process.

To every caregiver, seek help, seek support. Build alliances with teachers and therapists, join parent groups, connect with other families. Take your child out into the world and, in doing so, teach others how to embrace differences. I wrote my book not just to share Tylor’s story and how he formed an everlasting bond with his sister, but to remind the world that people with disabilities have emotions, dreams, and the capacity to connect.

As Benjamin Franklin said, "If you would not be forgotten, as soon as you are dead and rotten, either write things worth reading or do things worth writing." In this journey, I strive to do both.

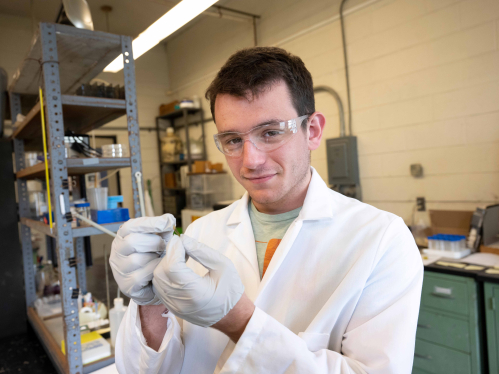

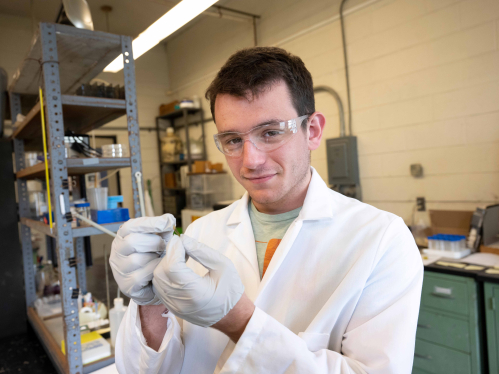

Dante Migliaccio

Class of 2025

School of Engineering

Rutgers-New Brunswick

“You don’t need accommodations, you’re smart! You’ll be fine!” This is a phrase I have heard throughout my undergraduate career, whether it be from family, friends or people I considered mentors. This is a phrase usually followed up by people bringing up my academic/professional success, but what they fail to acknowledge is that a lot of the barricades I have experienced have been in part due to my epilepsy and other issues that programs through the Office of Disability Services (ODS) have been able to help me navigate and find solutions to the problems.

One primary example of this is exam accommodation. I did not use the accommodations for my first set of exams, thinking, “I am smart, I can do this!” When I first stepped into the exam room, I realized I messed up. The walls felt like they closed in, time just seemed to fly, and I lost the capacity to read. I ended up failing all three exams, brutally. I then realized that it could be based on my medications and then I immediately went to ODS to get accommodations. After that, the ability to have less stress concerning time, being able to have smaller environments, and the opportunity to take a break if I am feeling a flare-up moment has made me excel in every exam that I have taken since.

As a senior, getting ready to apply to graduate school in materials science and engineering, I can confidently say that it was these accommodations that have allowed me the best opportunity to excel in my college career. So yes, I may be “smart,” but it doesn’t mean I don’t deserve my right to have the accommodations to aid me in my endeavors. What should you take away from this story? In your life, except in ODS, people will not understand your conditions, even if they claim to. With this, people can make uneducated comments or remarks. It is important to not let these comments negatively affect you or solely change your identities.

Julia Sass Rubin

Associate Dean of Academic Programs

Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy

Rutgers-New Brunswick

My daughter was diagnosed with ADHD a year ago, as she was beginning her senior year at Rutgers. She had always been a very strong student but had struggled with turning work in on time. Once a deadline passed, it became particularly difficult for her to complete the assignment. After the diagnosis, we understood that these behaviors were a function of her neurodiversity.

Although the symptoms of ADHD vary, there are many common ones that can make it more challenging to meet deadlines. For example, difficulties with starting tasks and with task organization and prioritization; feeling overwhelmed by large tasks; and a tendency toward procrastination. Another frequent feature of ADHD is time blindness -- an inability to sense how much time has passed and estimate the time needed to get something done.

I had been a professor for 20 years by the time my daughter was diagnosed, but seeing higher education through her eyes has been a revelation. Things that academics routinely do assumed entirely new meanings as I began to understand how they create disproportionate challenges for neurodivergent students.

For example, many faculty members penalize work that is turned in late, either severely reducing the maximum points that can be earned or refusing to accept it at all. Rutgers students who can verify their diagnosis may request up to two additional days on assignments by submitting letters of accommodation through ODS. However, faculty have some discretion in granting such extensions and neurodivergent students who struggle with deadlines may find a two-day extension inadequate. Many neurodivergent students are also not diagnosed until after they graduate from Rutgers, so cannot take advantage of the accommodations.

I doubt that penalties for turning work in late enhance student learning or encourage greater engagement. Most likely, we as faculty adopt them because that is what we learned from prior generations of faculty or because it is more convenient for us. My daughter’s experiences at Rutgers have made me more sensitive to the negative impact of such taken-for-granted practices on neurodivergent students, an awareness that I plan to share with other faculty members.

Raven Diaz

Class of 2026

School of Arts and Sciences

Rutgers-New Brunswick

For over 20 years of my life, I can positively say people have often painted my existence with sadness, pity or a strange sense of humor, to say the least. It is almost like they believe my consciousness is not able to comprehend a condescending tone or belittling demeanor. Occasionally, I’ll play into it; giggle a little more, enhance my politeness even when not reciprocated, and paint my face with detachment from what is going on around me.

I believe a part of me does this to ignore the fact that these experiences are something out of my control when I have to engage with others who carry themselves this way. Another part of me believes I do it to keep this burning agitation and annoyance at bay, remain patient and calm with infinite amounts of grace to give. I do not believe the majority of people do this intentionally and I do not harbor these feelings for many, but disrespect is something I have learned not to ever tolerate. I think a lot of people do not think of me as a full person, which is why this behavior persists. Yes, they may say, “she has feelings too,” or “You shouldn’t say that, it’s rude,” etc., but I do not think many think beyond that.

I have feelings, thoughts, beliefs, experiences, and abilities that are not all jolly, innocent, depressing, or blissfully ignorant. I can be mean and nice. I can be extremely intelligent and uneducated. I can be quick to anger, and I can be sarcastic or practice patience or jump to conclusions. I was a cringey kid who read stories on Wattpad and thought I was a cat for a quarter of third grade. I was an anxious teen who hated giving class presentations and watched anime, and now I am a semi-confident college student who despises finals season and scrolls on LinkedIn for hours. Because when I say I am like everyone else, I am ”everyone else.”

Dustin Petzold

Assistant Director of Communications

Office of Communications and Marketing

Rutgers-Camden

People with disabilities generally want to be treated just like everyone else. I may look like I’m struggling to step off the curb, for example, but I’ve navigated hundreds of curbs just like it and know when to ask for help if I need it.

I would also caution able-bodied people against assuming that people with disabilities are more likely to strike up friendships or share common interests. I understand the impulse to make introductions between your friends with disabilities; it is important to both give and take advice and support with those who have confronted similar challenges. However, many people with disabilities already built this network from early childhood, through special schools, physical therapy programs, adaptive sports and other sources. As we age and develop our sense of self, we tend to prefer being seen for who we are instead of what we are.

I would much rather you introduce me to your friend because we both like standup comedy than because we both have cerebral palsy. Would you make the same introduction between two friends with red hair, glasses or size 14 shoes? People with disabilities are diverse, complicated and flawed, just like all the other 8 billion people on the planet. Take inspiration from us where you find it, but understand that, unlike the disabled movie characters who warm the hearts of everyone they meet, there is a lot more beneath the surface.

Amanda Casabona

Class of 2025

School of Arts and Sciences

Rutgers-New Brunswick

My experience as a person with a disability has been both enduring and rewarding. With a cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM), most signs of my condition, such as seizures, severe migraines, and potential brain hemorrhaging, are not apparent on the outside. This can make it challenging to acknowledge my own limitations and boundaries that come with a non-visible disability, leading to an ongoing internal conflict between keeping up with my daily life and quietly managing my condition.

One thing I would like people to know about my experience is that the balancing act between wanting to push myself and needing to recognize my limits is a continual learning process. Just as many people do not know I have a disability and limitations upon meeting me and come to learn about the circumstances over time, I too am learning how to balance these circumstances. Another aspect I would like people to know, especially those who are managing their own conditions, is that there is an immense sense of perspective that can be gained. Many moments can feel burdensome and testing, but through those challenges, I have also learned patience, perseverance, and adaptability—qualities that have helped me in so many other areas of my life and will continue to do so.

My disability has shaped me but is only one aspect of my life. I’ve continued my education and pushed forward despite the obstacles, and I am learning to redefine what strength looks like. I hope that by sharing my experience, others can be mindful of the continuously evolving challenges people face while also appreciating their strength.

Gita Sharma

Assistant Professor of Professional Practice

Rutgers Business School

Rutgers-New Brunswick

My older daughter, Mira, was born with cerebral palsy, a motor disorder that affects her ability to control movement. Although Mira is non-verbal, she is one of the most expressive people you will meet. Due to Mira’s spasticity, she cannot communicate effectively using assistive devices or sign language. Yet, those who spend time with her often remark that she “talks” with her eyes.

We want Mira to be seen as a whole person – beyond her wheelchair and orthotics. Like her peers, Mira is curious about the world around her and has strong interests, likes, and dislikes. She beams when people approach her to engage and give her enough time to express her feelings. There can be a delay for Mira to respond due to her motor impairment, but it is worth the wait!

We hope that now that Mira is a young adult, she has many opportunities to participate in the community. Whether making new connections at the day program that she recently enrolled in or volunteering one day a week at her old school, Mira touches those around her with her gentle demeanor. She has even inspired her father, an engineer and technology enthusiast, to embark on an endeavor to build a platform centralizing care management, care coordination, and communication called “MiraKare”—essentially giving a “wellness voice” to those unable to effectively communicate their basic needs effectively.

Being Mira’s parent and parenting her younger sister has taught me immensely about patience, compassion, and appreciating all individuals' unique talents and challenges. As an educator, I try to keep that empathy and encouraging mindset at the heart of my teaching and interactions with my students. We are grateful to our extended family, friends, neighbors, teachers, therapists, and dedicated caregivers (i.e., “our village”) for being a part of Mira’s journey into adulthood. Can’t wait to see what the future holds for Mira!