White Coat Ceremony Marks the Beginning of Students' Journey Into Medicine

New Jersey Medical School welcomed 172 students at its annual celebration

She didn’t know it then, but when Marisa Lazarus tore her ACL as a teenager playing soccer, the injury put her on the path to becoming a physician.

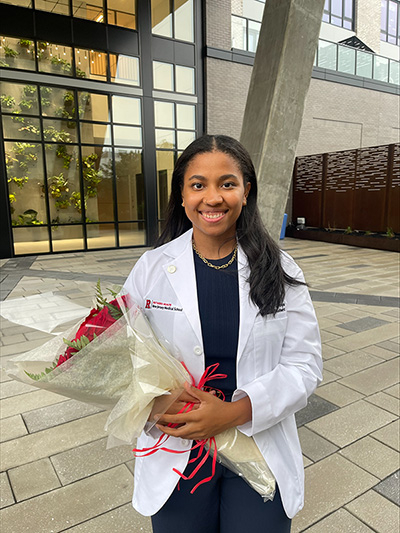

Lazarus officially began that journey last week when she donned her white coat during a ceremony at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark welcoming the newest class of students.

“Until that injury, my whole identity was tied to soccer,” said Lazarus, 23. “When I couldn’t play soccer, I started doing other things, and I realized I didn’t have to do this one thing with my life. It opened my eyes to my own potential.”

Her doctor treated her with the kind of respect usually reserved for adults, went over every scan to explain her progress and worked to ensure that she recovered fully to play soccer again. Lazarus, who grew up in Manalapan, N.J., was always a science kid, but that doctor made her realize that she also had a mind for medicine.

The Aug. 8 event was the second of two ceremonies welcoming medical students. Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick held its White Coat Ceremony last month, recognizing its incoming class of 165 students. The two schools may celebrate together in the future as Rutgers seeks a combined accreditation. If approved, it would create one of the largest leading public medical schools in the country.

“As each of you don your white coats, you aren’t just wearing an article of clothing,” Robert Johnson, dean of NJMS told the students during the Barbara and Norman Seiden White Coat Ceremony, which marked its 30th anniversary this year. “You’re donning a profound symbol that encapsulates your steadfast commitment to patient care and your unwavering pursuit of knowledge. I wish all of you the best as you embark on your medical journey.”

Maria L. Soto-Greene, executive vice dean of the school, recited the Hippocratic Oath as the future medical practitioners pledged to uphold the duties and principles of their medical profession.

As a young patient, Lazarus remembers what it felt like to lose her mobility and the care her doctor and his staff gave her.

“I felt so well taken care of,” said Lazarus, who graduated with a physics degree from George Washington University in Washington, D.C. “He made me feel super seen.”

Lazarus joins her aunt, who is a nurse manager at Monmouth Medical, as the only members of her family in the medical profession.

But for her classmate Schuyler Cross, becoming a physician seemed like the natural order to her life. Both Cross’s parents are physicians – her mother, Sheila Mosee, a pediatrician and her father, Patrick Cross, an oncologist. Her mother’s parents were also physicians: her grandmother, Jean Curl Mosee, was a pediatrician and her grandfather, Charles Mosee, a neurosurgeon.

Because she came from a family of physicians, Cross was aware of the issues facing the American health care system: overworked doctors, patients in underserved communities, an inadequate insurance system, and the ever-increasing cost of care. At first, she pursued a different route and received her biomedical engineering degree from Ohio State University in 2020. She liked the idea of working with her hands to create medical devices that help patients or conduct research, but it didn’t seem like the right choice for her.

“It was a little detached,” said Cross, 26. “You're producing these items and releasing them blind to the public. You don’t get to see how it helps. I just wanted something that allowed me to have more of that human connection and to engage with people and see how you’re contributing.”

In 2021, she began working as a medical assistant in an orthopedic office, giving her the opportunity and experience to recognize she indeed wanted to follow in her family’s footsteps. Those years also gave her the time to mourn the death of her brother, Jeremy, and the space to be able to face the challenges of medical school.

When she finishes medical school, Cross will be among a select group of doctors. As a Black woman, she will represent less than 3 percent of the profession.

“Until I started working in the field, I didn’t realize how important it is to have someone who can advocate for you and can offer a perspective that other people wouldn’t necessarily have,” said Cross, who is considering becoming a surgeon.

Charlie Williams also considered biomedical engineering when he came to Rutgers as an undergrad student. By the time he graduated in May 2023, he even had a lucrative job lined up, but he turned it down to pursue medicine. Just like Cross, he too, said biomedical engineering didn’t seem right for him.

“Have you ever heard of the saying ‘your career is your calling?’ I think that’s true for certain people and I’m one of those people,” said Williams, 23. “My career couldn’t be just a way to make money. I needed to give back. I needed to be fulfilled.”

Williams realized he wanted to become a physician after he went on a mission trip with Emmaus, a Christian ministry at Rutgers-New Brunswick in the summer before his senior year. On that trip to Georgia, he met a group of physicians, who loved their work despite the hardships that come with the job.

“They talked to us, and I got to hear their experience serving their community; they knew their community really well,” Williams recalled. “That was interesting to me because my previous internships were very detached.”

He returned telling his family that he was going to be a doctor. They were supportive and Williams took the medical school entry exam in January 2023. In the year since graduation, he has been working as a medical assistant at a cardiologist's office and a pharmacy technician at a hospital near his Cherry Hill hometown. Williams is still trying to figure out the field of medicine he’ll be going into, but it’ll likely be in pediatrics or emergency care.

“Having your occupation be a way to get involved in the community and be a way to get to know the people in your community, those were experiences I wasn’t going to have as an engineer, but something I could have as a doctor,” Williams said.